Several smaller crises have come together over the last few years to pose a much bigger crisis at Monaco’s Centre Hospitalier Princesse Grace, the Principality’s most important medical institution.

Bearing in mind the fact that CHPG also serves a population stretching from Beaulieu-sur-Mer to Menton, the seriousness of the problem is a major concern, too, beyond Monaco’s own tight borders.

It boils down to one combined challenge – finding suitable qualified staff.

Employees of CHPG face the daily challenges of commuting to work in Monaco, finding affordable parking if they come by car, and the lack of public transport options early in the morning and late in the evening if they don’t. Commuting is almost unavoidable, given the virtual impossibility of finding housing in Monaco, and increasingly in neighbouring communities, such as Beausoleil and Cap d’Ail, where housing costs have risen sharply.

In addition to the practical barriers faced by employees, there are other, structural, factors at work.

Benoite de la Sevelinges

Undoubtedly, the coronavirus lockdowns have not helped, as more employees in all sectors enjoyed the benefits of working from home. As outlined by CHPG’s director, Benoite de la Sevelinges: “The current generation does not want to work on weekends or at night. Young people and people in general want to spend more time with their families. It is a trend that is societal. We can criticise it. I think it’s up to us to adapt.”

She also feels that salaries must enter into the equation: ”It isn’t enough to tell (staff) that their profession is magnificent, and that what they do is extraordinary. The recognition must also be financial.”

Christophe Robino

Monaco’s Minister of Health and Social Affairs, Christophe Robino, himself a doctor by profession, echoes her sentiments, saying that since the coronavirus crisis many employees are prioritising their quality of life and looking for employment in sectors that are less challenging and the hours less burdensome. The minister also points out that training courses for nursing staff are full, and that there is no immediate crisis. Every year, 35 nurses graduate from the nursing institute in Monaco, he adds. However, the situation is being closely watched, he says.

He emphasised that salaries are not the major determinant for would-be employees and that the health care sector in Monaco shares many of the same problems as the hospitality industry. The two sectors are planning to hold talks to investigate how they might work together to find solutions.

On a day-to-day basis, not all CHPG’s problems are so invisible to patients. Anxious parents taking sick children to the paediatric emergency post at the hospital in recent weeks have found only one children’s specialist on duty and waits of up to six hours or more at weekends. One doctor told a patients in early December: “On days like this I want to hang myself.”

On a political level the crisis is a major talking point in the run-up to National Council elections on February 4 and the Government is under pressure on the issue.

However, there is one ray of sunshine, and that is the introduction of a four-day week. Such a move would go a long way to satisfy the non-financial demands of health professionals.

“We therefore hope to be able to deploy the four-day week in many sectors in 2023. This is important, because the private sector is starting to offer it,” Mme de la Sevelingues told Monaco Hebdo magazine.

There is general agreement that Monaco must continue to look closely at its much-vaunted attractivity – of which Princess Grace Hospital is a part – in an increasingly competitive world. Four-day week or not, the challenges are not going to go away any time soon.

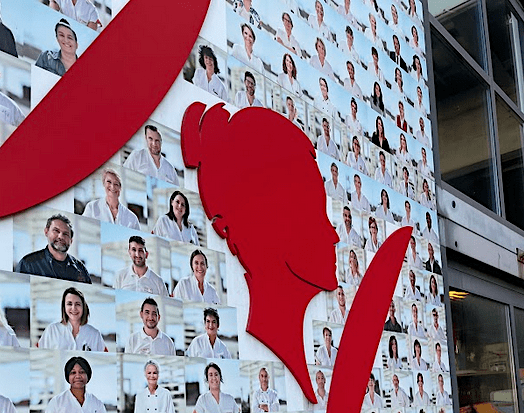

TOP PHOTO: Jan Fabricius-Kristensen